Minecraft to 3D

A pipeline that converts any Minecraft world into a high-quality polygonal scene for major 3D engines. Presented at SIGGRAPH 2025.

Project Details

I’ve always loved that Minecraft is basically a social 3D sketchbook. You can rough out a level with friends, prototype a dungeon in an evening, or block a whole environment with nothing but cubes and a vague idea of lighting. But the moment you try to take that world out of Minecraft, the spell breaks. A raw export is either an absurd triangle mess (every block turned into geometry) or a brittle file that technically imports into Blender/Unreal/Unity but looks jagged, heavy, and unusable. Your “village” isn’t a village; it’s just millions of cubes with no meaning.

Minecraft to 3D is my attempt to build the missing bridge. I wanted a workflow where Minecraft stays what it’s best at: layout, scale, and playful iteration, while the output becomes something that modern engines actually want: clean polygonal surfaces, coherent assets, and a scene that opens without the usual cleanup rituals. The goal isn’t perfect preservation of Minecraft’s cube-ness. The goal is preserving intent: object locations, orientations, and tags survive the translation, while the representation upgrades into something you can light, shade, and ship.

Inspiration

The motivating feeling was simple: Minecraft worlds often deserve better rendering. People build incredible spaces: campuses, castles, whole cities, and then those ideas get trapped behind the game’s rendering style and voxel geometry. I wanted a button that turns “voxel draft” into “production scene,” the same way a sketch can become a painting once it’s in the right medium.

Overview

Minecraft to 3D works by refusing the obvious solution. Instead of meshing every cube, it treats a Minecraft world like a scene that needs interpretation: what is terrain, and what is an object? That single decision changes everything. Terrain becomes a continuous surface (so lighting and traversal behave normally). Recognized structures become real mesh instances (so they can carry materials and detail). Water becomes its own exported layer (so engines can swap in their own ocean shaders). The result is a reconstructed world that still reads like the original build, but feels native in Blender and modern game engines.

The first “obvious” approach (and why I dropped it)

At the beginning, I tried thinking like a converter: “Minecraft is blocks, engines are triangles… so triangulate the blocks.” That immediately ran into three walls. First, scale: a large world becomes an explosion of geometry. Second, aesthetics: the staircase artifacts that look charming in-game become brutal under PBR lighting. Third, semantics: an engine can’t tell the difference between a tree and a pile of dirt if both are just cubes. I didn’t want a mesh. I wanted a scene.

That’s where the project pivoted from “geometry export” to “semantic reconstruction.” I stopped asking, “How do I convert blocks into polygons?” and started asking, “How do I preserve what the world means while changing how it’s represented?”

Proposal

I propose Minecraft to 3D as a focused end-to-end pipeline: load a Minecraft world, label canonical structures with a 3D CNN, rebuild terrain into a smooth height-map surface, substitute recognized objects with high-quality models from an external library, export water as a separate plane, and write the final scene in formats that open directly in modern tools. If it works, it feels like a clean translation: the world you built is still your world, just rendered in a different language.

Pipeline

To handle worlds at real scale, voxel data are streamed in 256×256 block tiles with a 20-block overlap, so structures crossing tile boundaries keep enough context to remain recognizable. On top of that I run a 3D U-Net trained on Minecraft’s canonical assets: oak trees, villager houses, desert temples, and related variants, to assign semantic labels. In reported evaluation, the network reaches 97.8% mIoU on isolated structures and 88.6% mIoU where structures intersect, which is exactly where things get messy in real builds.

That labeling step produces something I care about more than a pretty visualization: an object list. It’s lightweight, but it’s the spine of the whole export: block-accurate position, three-axis orientation, and any auxiliary tags (like structure orientation metadata). Once you have that, the world stops being “just voxels” and starts becoming a set of placeable things.

After segmentation, I hide the non-terrain voxels and rebuild the ground. The stepped terrain is up-sampled with trilinear interpolation, then smoothed with an anisotropic Gaussian filter to remove staircase artifacts. Because tiling can introduce seams, tiles are cropped back to their original bounds and merged with a Poisson blend, which suppresses seams without destroying the coarse relief. This is where the export becomes cinematic: the terrain stops catching light like a Lego staircase and starts behaving like a continuous landscape.

Then I do the swap. Each recognized object drives a query against an external model library to retrieve high-quality geometry matching class, scale, and broad proportions. Before placement, every model is rigidly aligned and normalized to the local ground patch so it sits flush: no floating temples, no half-buried houses. Water gets exported separately as a flat mesh at the recorded sea level, because water is a shader problem, not a geometry problem. Engines can replace that plane with their own ocean rendering or keep it intact for stylized looks.

Performance

This pipeline only matters if it’s fast enough to feel like part of a creative loop. On an RTX 4090, processing a 1 km² map (about 65 million blocks) takes 147 seconds, and stays under 3.2 GB of system memory thanks to a sparse-voxel octree. Most of the time is CNN inference (about 84%), with the rest split across height-map synthesis, Poisson blending, and model placement. Exported scenes open cleanly in Blender 4.1, Unreal 5.4, Unity 2023 LTS, and Godot 4.3, which was my practical definition of success: it imports, it’s intact, and it doesn’t fight you.

Results

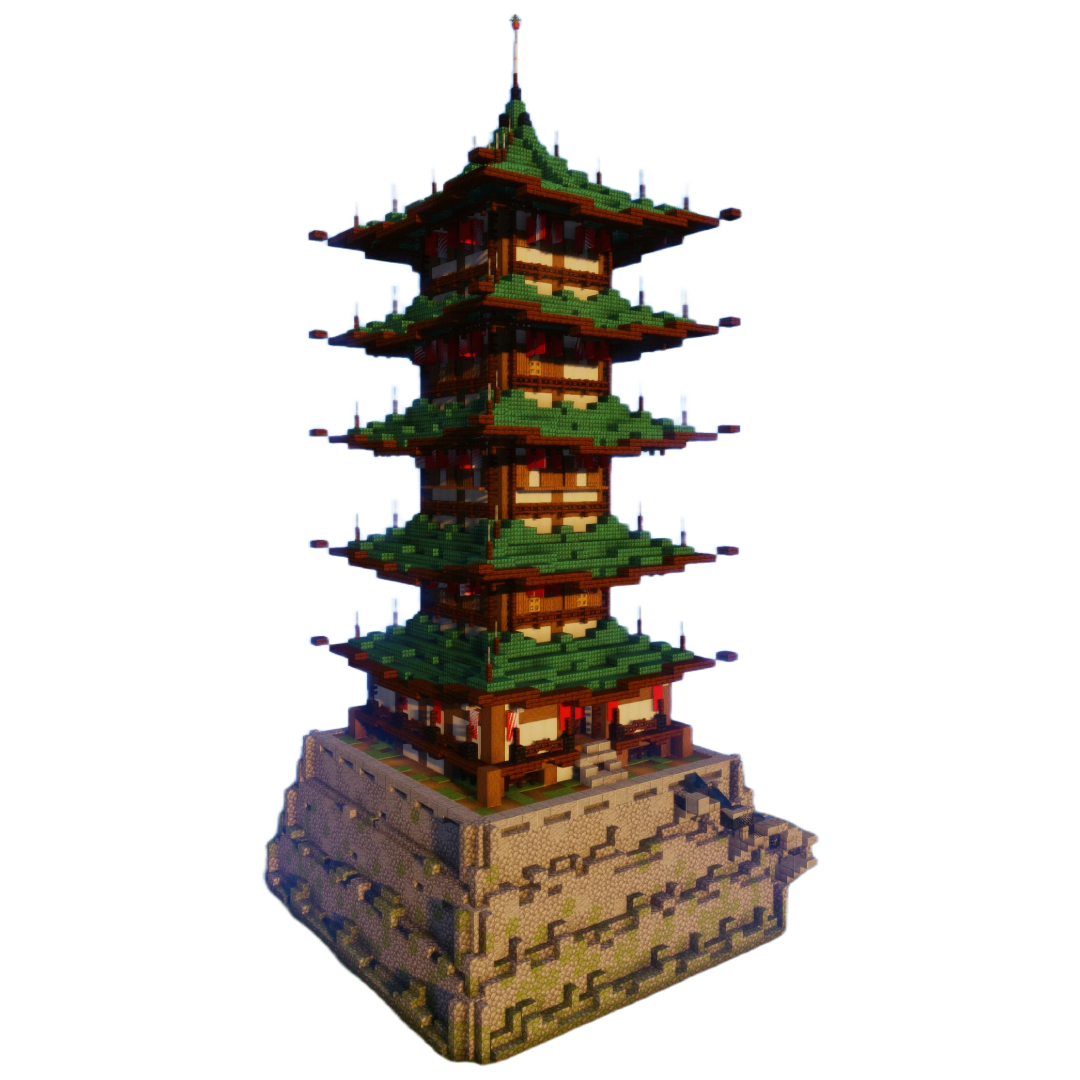

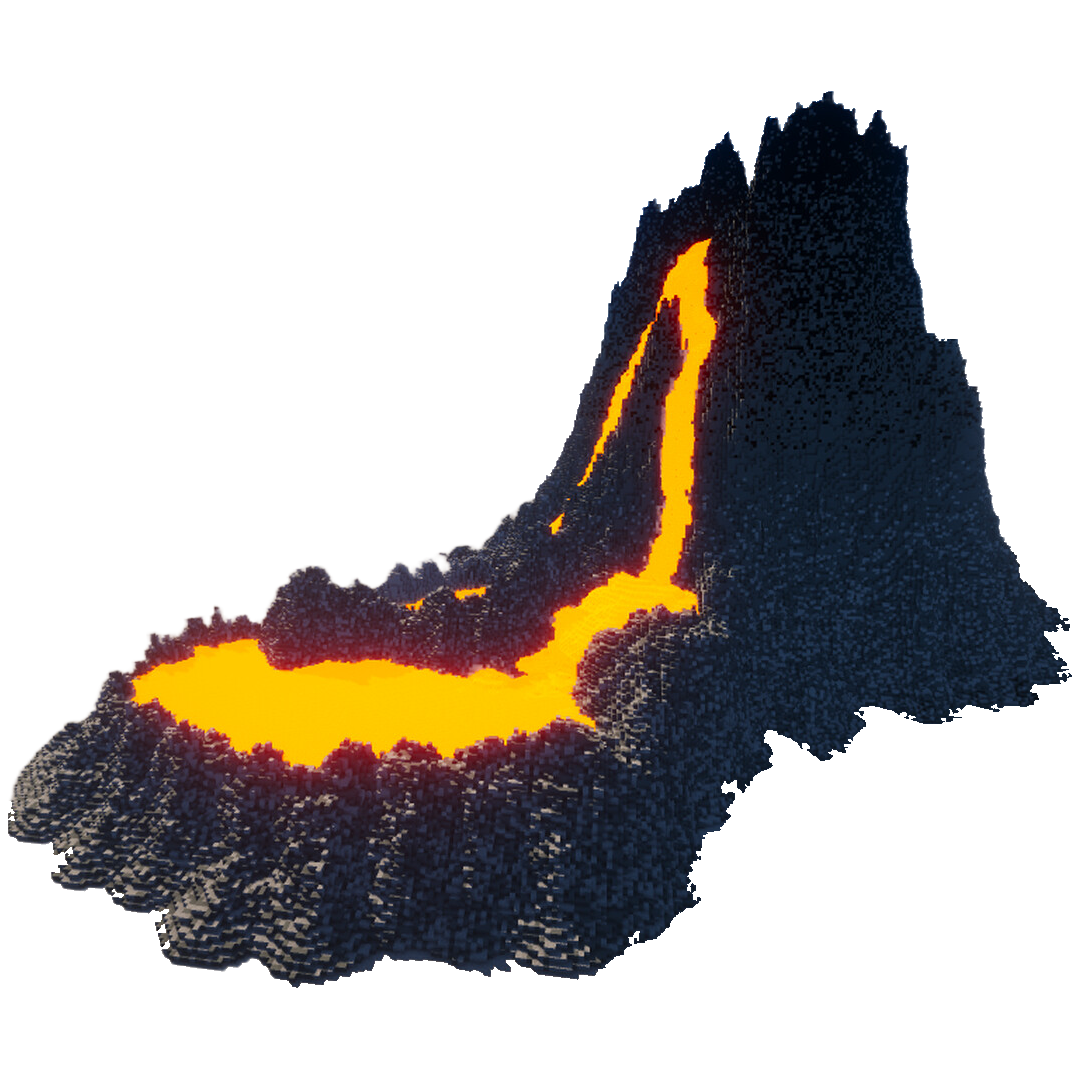

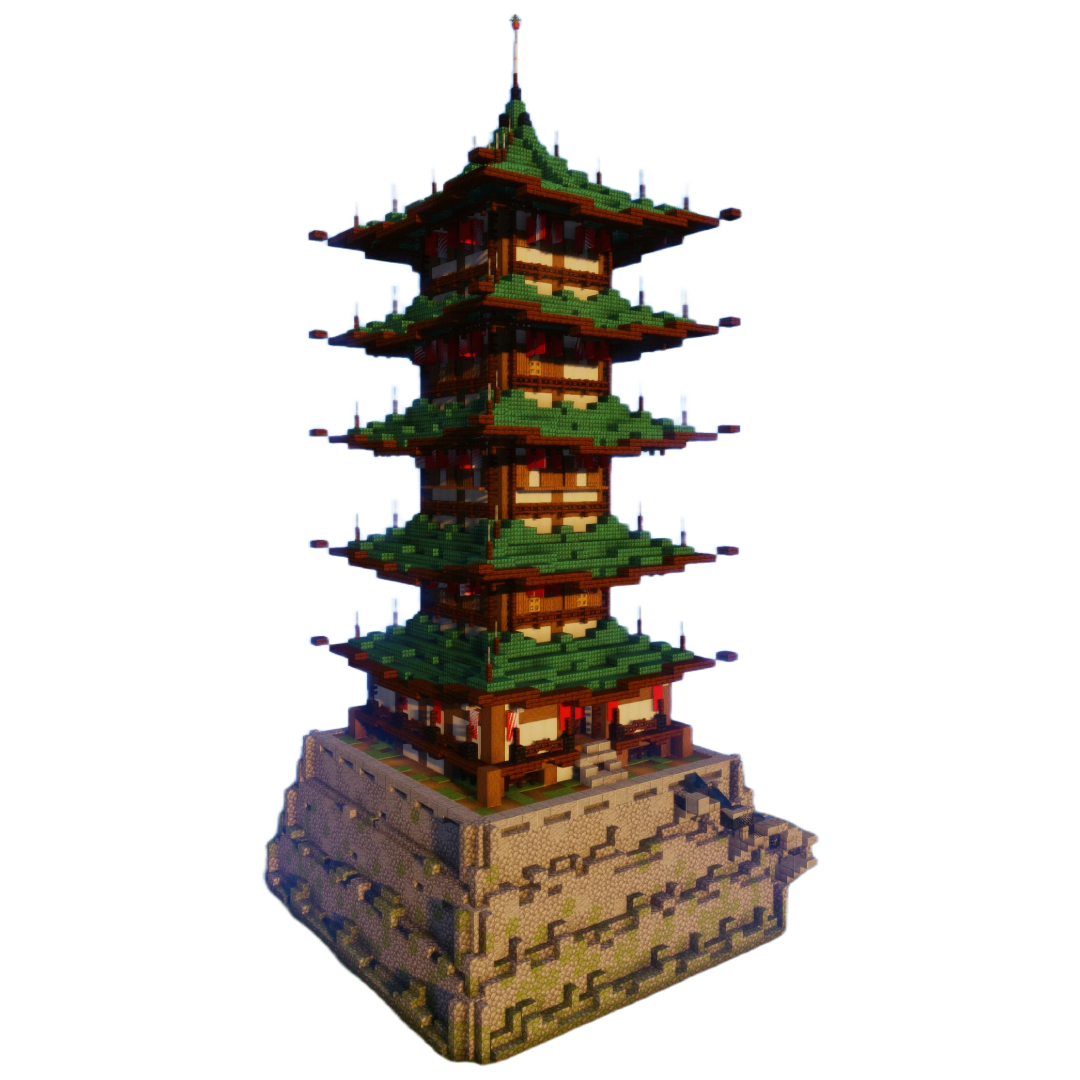

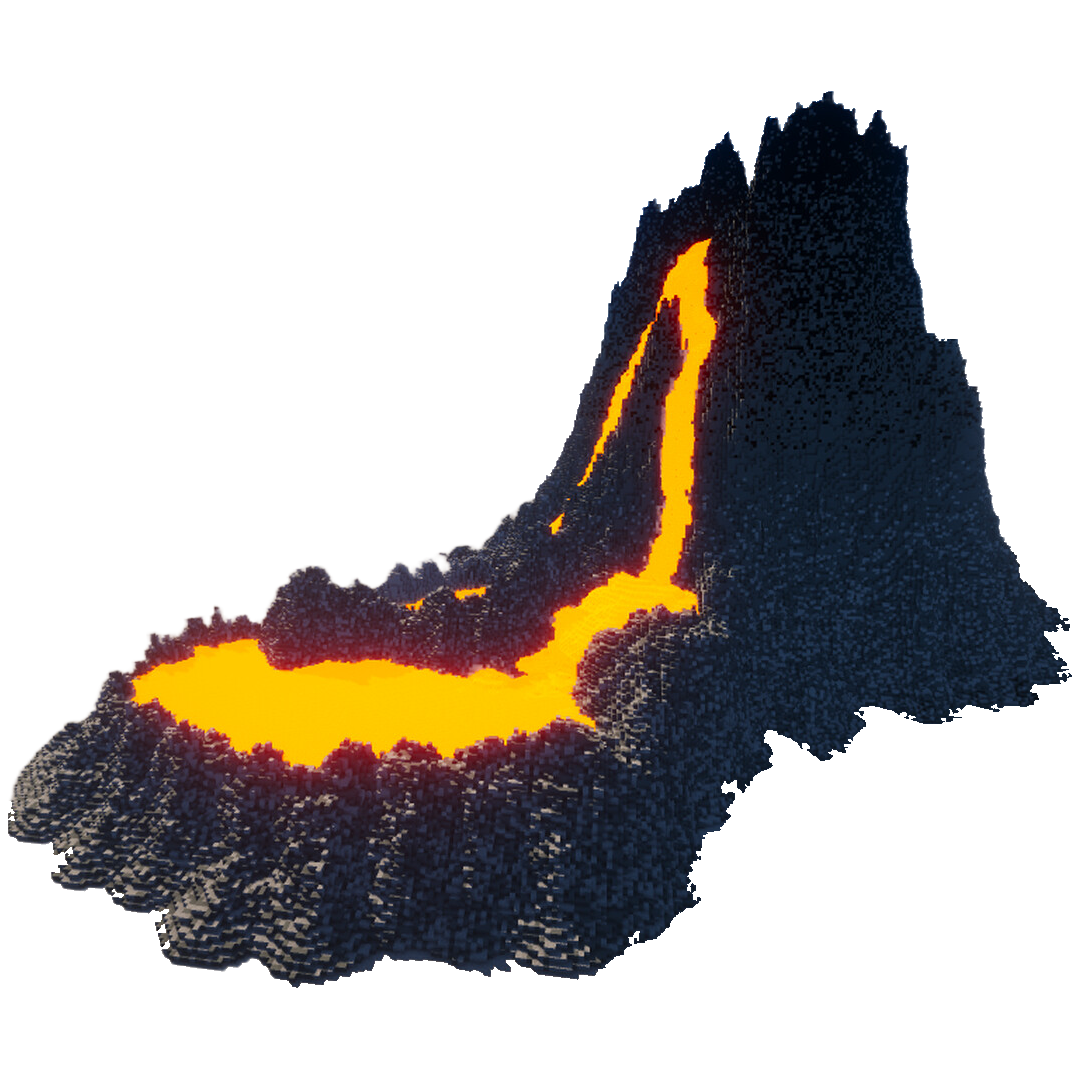

These comparisons are the moment the project “clicks” for people. The top side is the original Minecraft world, with all the blocky charm and constraints. The bottom side is the reconstructed version, where the same layout reads as a high-fidelity environment you can render and iterate on in a modern engine.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Before and after comparisons: each pair shows the same scene in Minecraft and in the reconstructed high-definition engine-ready version.

What surprised me (and what didn’t)

The most surprising part wasn’t that smoothing helps, it’s that smoothing is editorial. Heavy smoothing makes worlds look gorgeous, but it also quietly erases the little bits of block language people use intentionally: decorative patterns, crisp stairs, micro-steps that signal design. Lower the filter strength and you get back detail, but you also get bumpier terrain that can feel awkward for first-person navigation. There’s no single “right” setting, because it depends on whether you care more about cinematic readability or Minecraft fidelity.

The other predictable limitation is scope: the pipeline recognizes the default block set and canonical structures. Custom or modded blocks fall back to “terrain” and don’t receive substitution. And intersecting structures are still hard: when builds overlap densely, the network can merge labels and pick the wrong replacement. These failures aren’t random; they’re the cost of treating a messy creative world as something that must be neatly parsed.

Applications

This is the part I built it for. Indie teams can prototype a level in Minecraft, run export, and keep building in their engine with their own art assets. A 3D artist can block composition and scale fast, press one button, and spend time on lighting and shading instead of manual remodeling. Educators can generate cinematic fly-throughs of student worlds without forcing a full DCC workflow upfront. Virtual production teams can move collaboratively designed block sets into engine space with minimal handoff. The common thread is speed: Minecraft remains the playful front-end, and the pipeline turns that play into something production-compatible.

Future work

The next version wants to be less “canonical Minecraft” and more “Minecraft as a medium.” I’m training on community-created structures to extend beyond default assets, because that’s where Minecraft creativity actually lives. I’m also experimenting with on-demand AI-generated geometry, so substitutions can match style prompts or concept art rather than selecting from a fixed library. And the big technical obsession is an adaptive smoothing filter: something that preserves critical block detail where it communicates intent, while still eliminating staircases where they only add noise.

Discussion

Minecraft to 3D is a translation project more than a conversion project. Minecraft encodes spatial intent in cubes because cubes are fast and social. Modern engines encode believability in surfaces, materials, and lighting. This pipeline tries to preserve the meaning of a world while changing its form, keeping layout and semantics stable while upgrading representation into something you can render, edit, and ship.

It also taught me that “high fidelity” isn’t just adding detail. Fidelity is choosing what to keep. The moment you smooth terrain, you’re authoring the world. The moment you substitute an object, you’re imposing a style. In that sense, the pipeline isn’t just a tool, it’s a curator that decides which parts of Minecraft’s chaos become structure, and which parts become surface.

Special Thanks

Minecraft™ and related assets © Mojang Studios (2025). Minecraft™ screenshots, textures, or other Mojang assets (or derivatives) shown are used for educational research under Mojang AB permission per the published Minecraft™ Brand and Asset Usage Guidelines v2.1. This work is not affiliated with or endorsed by Mojang AB. Thanks to the open-source asset community; all 3D models shown are CC0.